There has been much focus on Italy and the Balkans here on the blog lately – and I have more to say about both. But I thought we’d leave all that for a bit, i.e. until I’m in the mood. Today, my mood wants me to focus closer to home, on what is one of the most special places in Norway.

We are at the foot of the Hardangervidda plateau, in the town of Rjukan, in Telemark county. If Telemark sounds familiar to you, you may have heard about a Hollywood action flick about the heroes of Telemark – and I’ll get back to that. Or you might be familiar with Telemark skiing. Or skiing in general, actually. Telemark is home of the sport. The modern day version, that is. Skiing has been around for much longer, of course. 1,200 years ago, during the Viking Era, people here used skis as an efficient means of transport – and to play in the snow. Even earlier, rock drawings from 4,000 BCE show people on skis. But I digress.

Industrial heritage

This is – or rather, was – a power plant, run by the Norsk Hydro company, at Vemork near Rjukan.

Idyllic setting for a factory, isn’t it? Well, this is Norway, you expected that, right?

Rjukan is surrounded by a dramatic landscape with rivers, valleys, lakes, waterfalls and mountains, including the characteristic mountain Gaustatoppen, where you can climb to the top – or take a Cold War era cable car up, inside the mountain, all James Bond like.

Rjukan (pronounced Rookan) is an old industrial town and has earned World Heritage status as a consequence of that. And yes, that is interesting – but there is something even more thrilling at play here. Rjukan, you see, is where 10 local lads helped save the world, one cold February day in 1943.

Industry at Rjukan

But first, the heritage site.

Industrial heritage is not something I was all that taken with originally. I’m usually more interested in people than machines. However, the more of these sites I explore, the more I realise industry is just as much about the human aspect as it is about technology, maybe even more. The people who work there, their families, their society, the towns where they lived their lives.

The Rjukan-Notodden Industrial Heritage Site comprises hydro-electric power plants and workshops, factories and labs, transmission lines, transport systems (a railway line and a ferry crossing on Lake Tinnsjø), and two company towns: Rjukan and Notodden.

We are now in the early 1900s. World hunger is a tragic reality and artificial fertiliser is needed to boost agriculture. In 1911, Norsk Hydro builds a factory here at Vemork, to produce fertiliser from the nitrogen in the air. Waterfalls and rivers provide the necessary energy. Rjukanfossen (Rjukan Waterfall) is the foundation.

Rjukan Waterfall: once a very impressive sight, now most of it is diverted inside these pipes.

A byproduct of the hydrogen gas produced here was D2O (deuterium oxide), better known as heavy water. So Norsk Hydro – spurred on by Leif Tronstad, an eager professor of chemistry at the Norwegian Institute of Technology in Trondheim – begins another project, the production of heavy water. Vemork becomes the first and only place in the world where heavy water is mass-produced. The production requires huge amounts of water and power – which Norway has in abundance.

Why heavy water, you ask? What are its uses? Well, back then – in 1934 – it was not quite clear what heavy water could be used for, other than scientific research. But who knows, thought Leif Tronstad, perhaps the world might need it. And Harold Clayton Urey had just been awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for discovering deuterium, so this was fascinating stuff to research. And Leif was an enthusiastic scientist.

Rjukan, the company town

In the company town of Rjukan, you can see how the workers lived. It was essentially built from scratch. In 1907, this was a small impoverished farming area, population: 100. Just 13 years later, it had been transformed to a lively town of 10,000. And a modern town, too: flushing loos in every house as early as 1912.

And just like that, the welfare state was well underway in Norway. Turning water into power gave massive amounts of cheap energy, and the country went from relatively poor to very rich in 100 years.

Rjukan town centre, with the rather monumental Såheim hydroelectric power station from 1915 in the background.

Left: The listed/protected Rjukan Baptist Church building, now mostly used as a concert venue. Right: Rjukanhuset from 1912, assembly hall for the Labour movement in the early days. Today it houses a cinema, a school of music and performing arts, a gallery and a cafe, as well as serving as a house of culture and venue for meetings and parties. Such a cool building!

War time sabotage

I promised you an even more thrilling story. It’s all about disruption. Rjukan, you see, was the site of one of the greatest acts of sabotage against Nazi-Germany during World War II. Had it failed, the fate of the world might have been quite different.

It’s an exciting story of heroism. So exciting, in fact, Hollywood made a film about it in 1965: The Heroes of Telemark, starring Kirk Douglas. The film is a bit sappy; it’s Tinseltown, after all. There are several documentaries that tell the story much better.

Heavy water

Remember Leif Tronstad, the passionate professor, and the only factory in the world where heavy water was mass-produced?

In the 1940s, Nazi-Germany is working on developing nuclear weapons. As it turns out, heavy water is a key component in building a nuclear reactor.

Each molecule of H2O (ordinary water) consists of 2 hydrogen atoms and 1 oxygen atom. So does D2O (deuterium oxide, aka heavy water). So how are they different? The answer is inside the hydrogen atom. In normal water, the nucleus of the atom contains only a proton. In heavy water, the nucleus has a neutron as well, making it, well, heavier.

Nuclear reactors run on uranium, a metal found in – and mined from – ordinary rocks. However, this natural uranium, called U-238, is not enough to sustain the chain reaction needed for nuclear fission. So most nuclear reactors run on an enriched version of uranium (U-235), which is expensive to produce.

This is where heavy water comes in. When you use heavy water in the reactor, the much more available U-238 is sufficient.

On 9 April 1940, the Nazis invade Norway. They soon seize control of the factory here at Vemork, and are now in possession of heavy water, as well as a brilliant production facility, designed by none other than our friend Leif.

Operation Grouse and Operation Freshman

Can you imagine Nazi-Germany with nukes? The thought alone is pure horror.

Meanwhile, Leif is on army duty. He could have worked with war-related research, but he prefers being an active soldier, and soon advances to the rank of major in the Norwegian High Command, operating from exile in London.

Leif Tronstad is … a brilliant scientist with a brilliant mind, but all he wants to do is be parachuted back into Norway to fight on the ground against Germans.

Britain has recently established SOE, a secret organisation to conduct sabotage and espionage behind enemy lines. A network of Norwegian soldiers in exile is set up around SOE. They are known as Kompani Linge – a Norwegian branch of the SOE, you might say. Their mission is to execute commando raids in Norway. Leif is the mastermind behind the raids, most famously Operation Gunnerside. More on that in a bit.

We are now in October 1942. The Allies cannot let the Nazis succeed in creating nuclear weapons, and a plan to destroy the heavy water factory is put into action. A front party – 4 locals – is sent over to do reconnaissance at Rjukan. Operation Grouse is afoot.

A month later, it is followed by Operation Freshman, where British Royal Engineers in two gliders and their tugs are sent off to reconnect with the front party and blow up the factory. Afterwards, the plan is for them to get back to England through neutral Sweden.

But but but… you say? Isn’t the Swedish border at least 300km from Hardangervidda? A local with exceptional outdoor skills – and skis – could do that. But highly trained as the engineers no doubt were, they had little local knowledge. They were not used to operating in deep snow. 300km through the snow, and without skis? What were they thinking over there in London? How was that to be?

Sadly, they never find out. It is not to be, you see. They don’t even get as far as the Rjukan area. Bad weather at the Norwegian coast causes the rope between the first tug and glider to snap. The glider crash-lands and the tug barely manages to return to Britain. 3 of the 17 in the glider are killed in the crash; the rest are caught by the Nazis, then interrogated, tortured and executed.

An even worse fate awaits the other tug-glider combination. The weather leads the tug to release the glider before it crashes into a mountain, killing all on board. The glider also crash-lands. The pilot and co-pilot are killed on impact. The survivors are captured and executed.

Altogether, 41 young British soldiers dies in Operation Freshman. And up on the Hardangervidda Plateau, the four locals in the front party await the planes that never arrive.

Operation Gunnerside

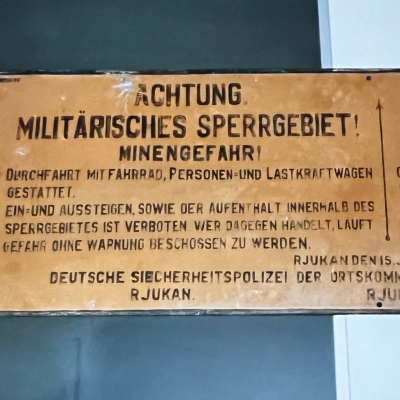

The Nazis have found a map on one of the captured soldiers. They now know the plant at Vemork is the intended target, and ramp up security. Several sabotage attempts are made in the following months, none of them successful.

But wait a minute: aren’t the 4 from the front party still operational? Let’s use them. A further 6 SOE-trained locals parachute onto Hardangervidda. They 10 of them spend the next months on the desolate rocky plateau, much of it outdoors in sub-zero Fahrenheit temperatures. They mostly have to hunt their food. Fortunately for them, reindeer roam Hardangervidda. Their job now is to gather knowledge and practice necessary skills.

Four months later, on 27 February 1943, 9 of them move on towards Rjukan and the factory at Vemork.

Now, this is a very remote spot. The plant is located on the edge of a cliff, a 150-metre drop, ice-clad in winter. It is a very difficult place to reach, never mind attack from the ground. But the saboteurs scale the icy crag, sneak into the ravine and cross the half-frozen River Måna, all without being spotted by the guards.

Our 9 guys, led by 23-year-old Joachim Rønneberg, are equipped with intelligence down to the minutest detail, thanks to Leif’s meticulous preparation. They reach Vemork, cut the locks on the gate, enter the plant, and get into the basement where the heavy water is – all without setting off a single alarm.

There, they place 4.5 kg of explosive charges along the heavy water facility. To make sure the basement will explode, Joachim cuts the fuses down from 2 minutes to 30 seconds, set them alight, and gets everyone out just before it blows up.

Reconstruction of the sabotage party at work – The Norwegian Industrial Workers’ Museum at Vemork.

The whole operation takes 30 minutes, and not a shot is fired. No one is killed or wounded. Even General von Falkenhorst, head of the German invasion and occupation of Norway, is impressed. The most remarkable coup I have ever seen in this war, he said. It takes character, I think, to openly admire the enemy’s skills. But then, von Falkenhorst was military, and not really political. He seemed to have no time for Quisling (the self-proclaimed Minister President of Norway during the war) and his Nazi collaborators.

In the days that follow, thousands of German soldiers search for the saboteurs, but no luck. Fully armed and dressed in uniforms, the boys are on their way to Sweden on skis. Crossing the valleys of southern Norway takes them 14 days.

Operation Gunnerside is a success. Massive amounts of heavy water is destroyed. Those young’uns helped prevent Adolf and his gang of Nazi thugs from developing the nuclear bomb.

Operation Tinnsjø

The railway ferry M/F Storegut (meaning Big Boy) carry passengers and cargo across Lake Tinnsjø today.

But the Nazis don’t give up so easily. After the sabotage, they want to rebuild the facilities. Then, the Allies attack from the air. The USAAF drops 711 bombs on the area, of which more than 600 miss the target. The 100 or so that don’t miss, cause enough damage to put the brakes on production for a while.

We are now in 1944. Production has resumed. Meanwhile, the USAAF has begun a series of raids on the factory. Enough is enough, say the Nazis. Time to take the remaining heavy water and important components to the homeland and continue production there.

Naturally, this cannot be allowed to happen. But how to stop the Nazis this time?

First step of the transport to Germany is by railway ferry – the D/F Hydro – across Tinnsjø, one of Europe’s deepest lakes. The sooner, the better, thinks Milorg (the local resistance organisation), and affix a bomb to the ferry’s keel.

It works. The ferry sinks, but sadly with brutal collateral damage. In addition to 39 barrels of heavy water, 47 passengers are on board.

D/F Hydro carries two life boats. The water is ice cold. Locals jump in the freezing water and rescue several of the 47, but still 18 people perish: four German soldiers and 14 locals. Amongst the latter, are three teenage girls and 4-year-old Unni-Lise.

More than 70 years later, D/F Hydro is still at the bottom of Lake Tinnsjø, 430 metres down, almost intact.

The idea of nuclear weapons in Nazi hands is spine-chilling! It could all have gone so very, very wrong. Not just for those involved in these operations, but for the world.

But it didn’t. And here we are. In no small part thanks to Leif, Joachim & Co.

In October 1944, Leif Tronstad, our brilliant scientist-turned-equally-brilliant-soldier was parachuted down on Hardangervidda to lead yet another action on the ground known as Operation Sunshine. 5 months later, just 2 months before the war ended, he was shot and killed by a local Nazi collaborator. After the war ended, he had a military funeral and was awarded several Norwegian and international decorations. Britain honoured him with the Order of the British Empire and the Distinguished Service Order, France gave him the Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur and Croix de Guerre, and the USA awarded him the Medal of Freedom with bronze palm. Curious what he would have thought of all that, had he been alive.

…the results achieved, which demanded the highest courage, organizing capacity and scientific skill, contributed directly to the speedy victory of the Allied Nations, besides saving the region which came to be known as “Southern England” from an even longer and more severe ordeal than it actually endured. He received the Order of the British Empire for his outstanding services.

Professors at Cambridge, Sir Eric Keightley Rideal and Ulick R. Evans – Nature Magazine 21 July 1945

Joachim Rønneberg became a journalist and worked for NRK (Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation) until 1987. He was very uncomfortable with the hero focus (as were the others), and did not want to be in the film about the heavy water sabotage. But as the years went on, and a new generation grew up, unaware of much that happened during the war, he got involved in dissemination work. During his lifetime, he was awarded numerous awards and decorations. On his 95th birthday, he was honoured with a statue in his hometown Ålesund, with several thousand people present. At 95, he was

still mentally sharp … and possessed of the unflappable calm that so impressed British military commanders more than 70 years ago.

Andrew Higgins, The New York Times

Joachim died in 2018 at the age of 99, as the last of the Gunnerside saboteurs. He was given a state funeral.

Norwegian Industrial Workers’ Museum

The heavy water factory closed in 1971. 16 years later, the power station was turned into The Norwegian Industrial Workers’ Museum. In the cinema there, you can watch the documentary If Hitler had the Bomb about the sabotage acts. You can also join a guided tour of the heavy water basement where the saboteurs went to work that February day in 1943.

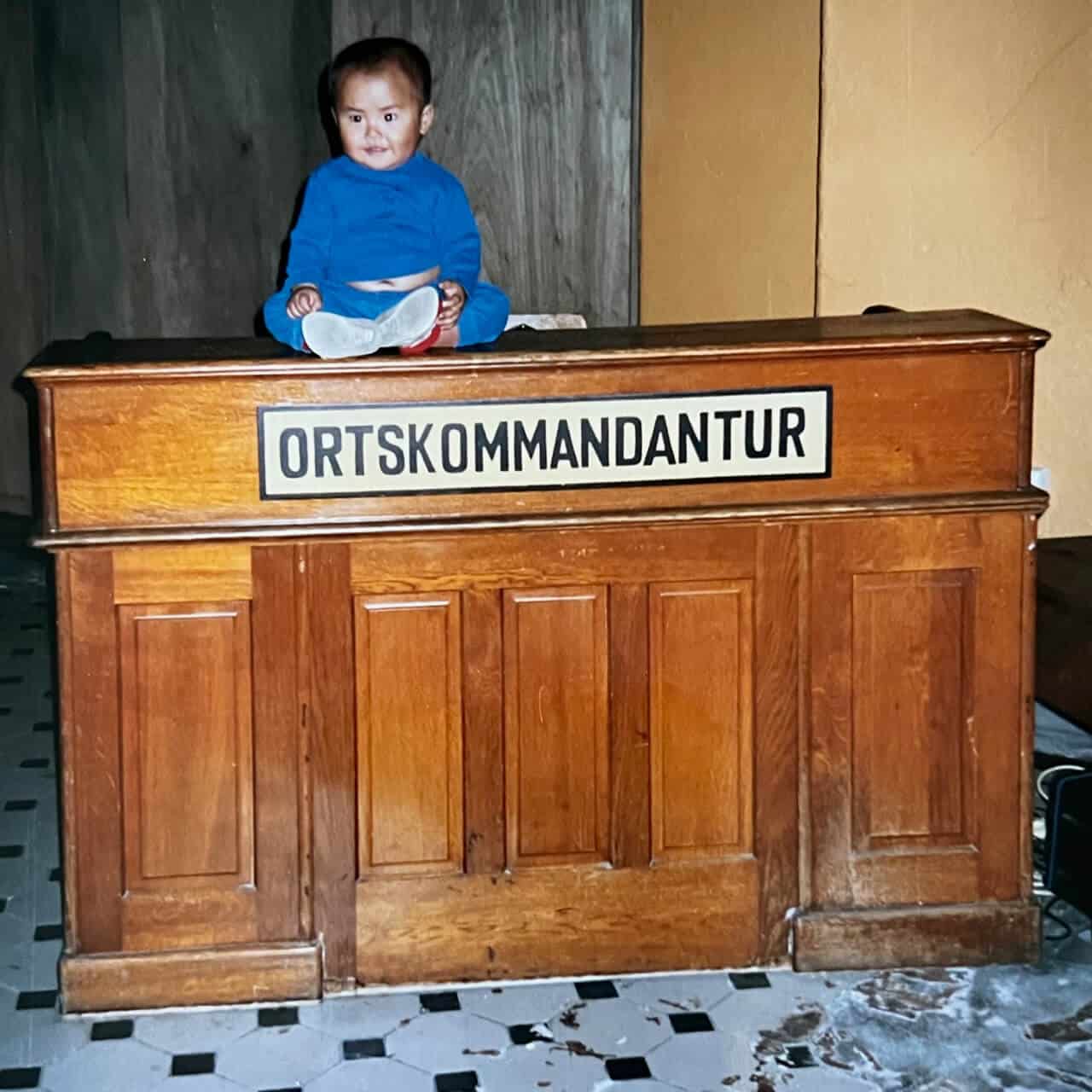

Taking over the desk of the local police commander at the Norwegian Industrial Workers’ Museum at Vemork. No more Nazis allowed here. Is that clear?!!

Other things to do in Rjukan

In Rjukan, you can hike in nature, amongst meadows, fields and flowers. You can also:

- join a guided tour in the footsteps of the saboteurs (you’ll be crossing the canyon) – on foot in summer and on snowshoes in winter

- ski (of course)

- ride horses

- ice climb up to one of the 192 frozen waterfalls in winter,

- bungee jump from the suspension bridge. 84 metres above the canyon, this is Norway’s highest permanent bungee

In the beginning of this post, I said Rjukan was one of the most special places in Norway. You have plenty of the spectacular nature the country is known for. You can explore industrial history and get a feel for everyday life 100 years ago, and see interesting Art Deco and Art Nouveau architecture. Best of all, you can hear about intriguing international war history – and the story of a few exceptionally brave boys whose actions had a far-reaching effect on the world.

Notodden

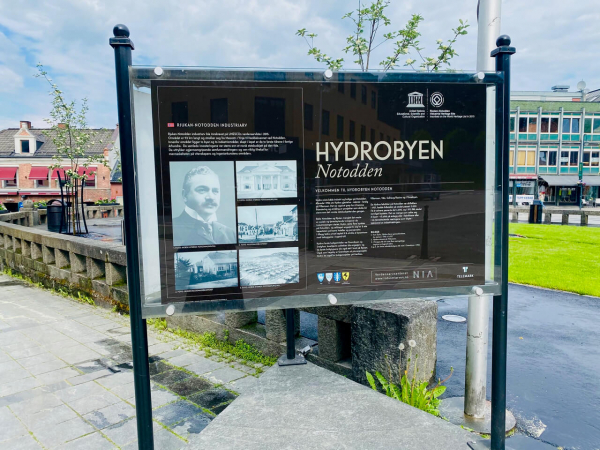

I mentioned there were two towns; the other one is Notodden, home to Norsk Hydro’s head office in the early 1900s.

Wandering around Notodden, apart from an info board about the industrial heritage, I don’t get much of a feel for the town’s industrial past. A guided tour could be an option.

Stasjonen kafé is worth a look and a coffee stop. The cafe is located in the town’s first railway station, an Art Nouveau building, and part of the world heritage site.

Notodden has other things going for it as well:

- The Telemark Canal: take a leisurely 80-km journey on the M/S Henrik Ibsen or the M/S Victoria through the locks from Skien to Notodden. Or you can take your own boat, canoe or kayak. (Despite having lived in this country practically all my life, I still have not done this journey. Next summer, promise. Now you can hold me accountable.)

- If you are here in early August, you can catch the annual Notodden Blues Festival. Artists that have performed here include BB King, Buddy Guy, Van Morrison… the list goes on.

- Another highlight is Heddal Stave Church, the biggest of Norway’s remaining 28 stave churches.

Heddal Stave Church