Nagorno-Karabakh: what images or memories does that name conjure up for you? Perhaps news from the 1990s, stories of war and upheaval, and again in the 2020s, when conflict flared once more?

To me, it always evoked a strange combination of fear and fascination; a name that carried both a whisper of peril and the thrill of the unknown. It was in the rugged mountains of the mysterious Caucasus, and it was a relic of the once-closed and oh-so-secret world of the Soviet Union. I felt both wary of, and irresistibly drawn to, Nagorno-Karabakh. What was behind the headlines? It was somewhere I wanted to see for myself.

It has taken a long time to write about this contested region. Making it non-political and fair to both sides has been challenging. This is one conflict where (in my opinion) both sides have valid claims. In the end, I decided on a travel story, nothing more, nothing less. But first, a bit of reference:

Nagorno-Karabakh after the USSR: three decades of conflict and transformation

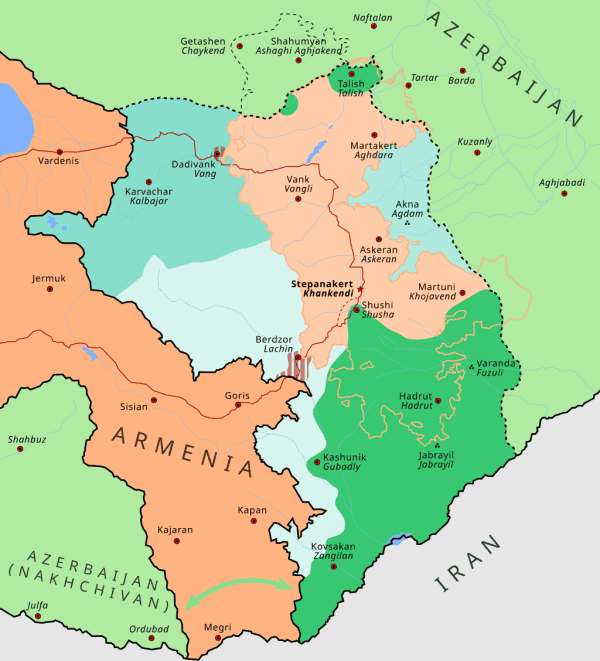

Mapeh, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the southern part of the Caucasus, mountains do more than divide landscapes. They divide eras. This is especially true in Nagorno-Karabakh, a region that has lived many lives in a single lifetime. Armenia and Azerbaijan have fought over this territory for more than 100 years.

Back in Soviet times, Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast was a culturally Armenian-majority region within the Azerbaijan SSR, shaped by centrally planned towns, collective farms, and that old familiar Soviet architecture. For decades, it followed the rhythms of the USSR: factories, cultural houses, hillside villages, dachas (summer cabins) in the forests. But beneath the surface, identity, language, and memory ran strong.

With the Soviet collapse in 1991, the region entered a new and turbulent chapter. The First Nagorno-Karabakh War shaped the region’s borders and emptied many towns, with major battles around Shusha/Shushi, Aghdam, and the Lachin corridor. The war ended in 1994 with Armenia winning, more than a million displaced Azerbaijanis, and 30,000 dead.

Almost 30 years later, the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War (2020, and again in 2023), ended with Azerbaijani victory and a mass exodus of Armenians.

Each conflict left its own imprint, turning Karabakh into a landscape of successive eras, each marked by its battles.

A journey across Nagorno-Karabakh through two worlds

Few places have changed as dramatically in a single decade as Nagorno-Karabakh. I first travelled to this area in 2017, when the region identified itself as Artsakh and felt like a small, self-contained world.

Returning in 2024, now under Azerbaijani administration, I saw a landscape transformed by reconstruction, new infrastructure, and a different political horizon. It felt less like returning to a place, and more like returning to a memory, rewritten.

This is the story of travelling the same road twice, in two different worlds, with two distinct realities inscribed across the same mountains.

Shushi/Shusha

2017 – ARMENIAN ARTSAKH

At the end of a journey across Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia, I was looking for a way in to this disputed territory. Marshrutkas made the journey from Yerevan, but when I was offered a seat on a bus full of Armenians from around the world, I was intrigued.

And so I find myself on winding roads where mountains curl around villages like protective hands, on a bus with Syrian-Armenians, Australian-Armenians, Lebanese-Armenians, Armenians from Quebec, Iran, Israel…

Then there is me. From Norway. Not Armenian. Just curious.

Yerevan to Stepanakert

Leaving Yerevan, the highway slips quickly into mountain country: steep gorges, apricot orchards, and narrow passes with villages where roadside vendors sell jars of honey.

The route winds south through Goris, where cliffside houses are stacked like stone terraces, before it climbs toward the checkpoint – the unofficial border – near Lachin. In the distance, I spot a monastery sitting improbably on a cliff. Traffic moves slowly, partly because of the terrain. The landscape demands the driver’s full attention.

The checkpoint is a breeze. Young soldiers are busy flirting with each other, and give us hardly a glance.

Snapping photos at a military checkpoint? Totally fine.

A visa is not required, but I ask for one anyway. As a souvenir.

For my fellow travellers on the bus, the journey appears to be as much emotional as geographical. I hear many stories, some funny, some sad.

I also get into arguments.

Past the checkpoint, the road is smooth, and the air sharpens as the road descends into pine forests and open valleys. Small towns and villages appear at measured intervals.

Stepanakert

Arriving in the capital; I feel as if I have reached a hidden enclave, remote but lived-in.

Stepanakert has Soviet architecture, flowers, tree-lined streets and sweeping views of the surrounding mountains. It is a small city, quiet, modest, easily walkable.

The Presidential Palace on Renaissance Square, formerly HQ of the Nagorno-Karabakh Regional Committee of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan on Lenin Square

Mass weddings and bride kidnappings

As I pause for a closer look at this sculpture, a local approaches. He must have noticed my puzzled expression, because he launches into a story about a mass wedding.

In 2008, to encourage a baby boom, a mass wedding took place in Stepanakert, organised by Levon Hayrapetyan, a wealthy Russian-Armenian. 700 couples tied the knot, with the promise of state support to the tune of USD 2,000 for each child born. There were rumours the ceremony included abducted brides, a practice not unheard of in Armenia, known as Aghjik Pakhtsnotsi (girl-kidnapping). Originally a children’s game, the term includes both cases of consensual ‘kidnapping’, i.e. eloping, and of coercive, violent stalking and abduction.

I am staying at the quiet, lovely Vallex Garden Hotel, along with some of my fellow travellers. We arrive in the early evening, and the gang is ready to party.

Shushi/Shusha

Next morning, I am up early to have a look around this peculiar breakaway territory. Some of the Armenians very kindly invite me to join them on a guided tour. We begin in Shushi (Armenian) / Shusha (Azerbaijani).

On the approach to town is a striking landmark: a T-34 tank on a concrete platform. This town was the most important Azerbaijani stronghold in the first Nagorno-Karabakh War, and it was captured by Armenians in 1992, using this tank. A stark, immovable relic, set against the vast mountain backdrop.

This 8-year-old girl and her 13-year-old brother have travelled from Canada with their mother, to meet up with grandpa who lives in Damascus. They are seeing each other for the first time since war broke out in Syria in 2011.

It is a quiet hilltop town, Shushi – with faded, fragile grandeur and views stretching for miles. Weathered houses along stone streets, art schools and little cafés overlook sweeping valleys far below. Ghazanchetsots Cathedral dominates the skyline. A fortress from the Persian Era stands guard over the cliffs.

Life moves slowly here. Children play near the cultural centre, artists sketch the old neighbourhoods, open plazas are filled with the sound of church bells and the wind moving through the trees. There is a low-key, contemplative energy here.

Friendly folks in Shushi

Gandzasar Cathedral

From Stepanakert, the road winds north past the village of Vank and up to Gandzasar Cathedral, originally a 13th century monastery. This is the most important Armenian-Apostolic church in Artsakh. The walls carry centuries of candle smoke and whispered prayers. A bit eerie.

Close to the church is the Lion’s Cave, a tourist attraction associated with local legends of strength and refuge, and restored by none other than Levon Hayrapetyan, of mass wedding fame.

Insta spot

Tigranakert, Aghdam, and ghosts of the past

We continue east to Tigranakert and Aghdam. The former is an archaeological echo of an ancient Armenian kingdom, with ruins stretching across a dry plateau. It is a quiet place – and a little spooky; all I can hear is my own footsteps on the stones.

The medieval fortress of Tigranakert – looking out on Aghdam

But the place that leaves the deepest mark is Aghdam, scene of several battles during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. Shots are frequently fired from across the border in Azerbaijan, says the guide. Do not go far.

Once the home of 60,000 souls, now it is a ghost town with hollowed buildings and streets consumed by grass. The twin minarets of a lonely mosque stand like two markers of a vanished world. The silence is so heavy it feels physical. I walk along boulevards that leads nowhere and everywhere at once. Aghdam is not empty. It is full of absence.

Back to Stepanakert

Returning to Stepanakert is like coming back to the living world. Just outside town, we stop by the iconic We Are Our Mountains-monument, carved from amber stone and a symbol of Armenian heritage. Locals call it Tatik-Papik, Grandmother-Grandfather.

Tatik-Papik

A new day

It is my last day in this territory. Before heading back to Yerevan and Armenia proper, I go for an early morning walk in the unusual little capital.

Metallic Grand Marquis or metallic Lada: what’s your preference? Me, I’m nostalgically drawn to this orange Moskvitch. It was a popular car in Norway in my childhood, along with Opel and Hillman and the VW Beetle, long before anyone thought they needed huge SUVs.

Friendly folks at the market:

Is that look saying ‘Enough with the snapping, buy the dress already’? I don’t know. We have no languages in common, and my attempts at Armenian, well…

I ask for a quarter kilo of raspberries, at least I think I do. But this lovely lady laughs so hard she nearly falls over, and gives me a big bag of berries, free of charge. Wonder what I really said…

Artsakh in a nutshell

That was Artsakh: fragile and remote. A land leaning into its past for identity, held together by monasteries, mountain roads, and quiet resilience.

I left, thinking I might someday return to the same place.

I was wrong.

2024 – AZERBAIJANI KARABAKH

The liberated territories

Seven years later, the land has changed its name, its authority, its rhythm.

This time, I am here with a group of fellow travel writers, bloggers, journos – all of us Norwegian. The trip is organised by Azerbaijani extreme traveller, Mehraj Mahmudov, under the banner of a peace tour of a former war zone. The intention is three-fold: to send a message of peace around the world, support landmine clearance, and promote tourism. Of course I’m curious.

We leave Baku at 04.00, as we have a lot of ground to cover.

Sun rising on the road to Karabakh

We enter the territory near Fuzuli International Airport, a glass-and-steel structure on soil that once held ruins. The highway leading out of it is newly constructed, smooth as an airport runway, pointing like an arrow toward the rising mountains.

The airport itself was built, along with two others, in just eight months. However, despite the efficient construction, the three airports are not yet in operation (as at May 2024), due to the challenges of landmine clearing.

As for Fuzuli town…

Shusha: the reframed city on the cliffs

The ascent to Shushi, now Shusha, feels familiar yet strange. The cliffs are the same; the road is not.

Shusha now has a more curated energy: restored mosques, clean squares, polished stonework.

Cultural institutions are reopened, and the fortress walls have been restored.

Statues of famous Azerbaijanis bear the scars of conflict, their surfaces peppered with bullet holes that stand as stark reminders of the city’s turbulent recent history.

But beneath the renewal is a profound quiet: a city rebuilt faster than it has been repopulated. One thing at a time.

Aghdam: the future city of the plains

In Aghdam, where I once was warned not to walk along the sprawling ruins because shots could be fired, a planned city is on the rise.

Wide boulevards are coming, new administrative buildings, and the old Juma Mosque (Friday Mosque) is being carefully preserved.

According to our guide, Armenians used the mosque as a cattle barn.

There are still ruins here, like the Aghdam Bread Museum, a significant historical museum dedicated to, well, bread, built on the site of an ancient mill. Three walls were destroyed by shelling in the first Nagorno-Karabakh War, and now, after the second, it is being restored.

Aghdam is a construction site of a future still waiting for its people. It is no longer the ghost city it was seven years ago. But dangers still lurks. We walk along a narrow path that has been cleared of landmines, and are told not to stray from it.

More about landmines in a bit.

Near Aghdam is a cemetery holding the graves of local victims of war.

Across the border in Armenia, are similar memorials. No one really wins a war.

Toghana

At night, we reach Toghana, where we stay at the Cennet Makhan Hotel, a peaceful refuge in the hills.

Ömar Mountain Pass: the raw spine of the Caucasus

Beyond Toghana, the road climbs into the Ömar Mountain Pass. The air thins and sharpens. At this altitude, snow is on the ground, even now in May. The land is majestic, indifferent, eternal.

Kalbajar and the Istisu Springs

Descending into Kalbajar, forests return, thick and deep. We are down to 2,225-metre altitude now.

In the early 12th century, a massive earthquake left behind thermal mineral-rich springs.

Love all the colours in the travertine terraces

Here at Istisu Springs, steam rises in pale ribbons, and for some of us, a dip under the cold skies is just what the doctor ordered.

There is a Soviet era sanatorium nearby, stuck between eras, neither restored nor demolished. But the water flows anyway, ancient and unbothered.

Minkand, Lachin, Qubadly

The southern arc of the journey winds through Minkand, Lachin, and Qubadly, villages scattered amongst steep valleys and meadows. Most are partially rebuilt; some are still skeletal outlines of former settlements.

I am now near where the former checkpoint was – and the press is following along

Zangilan: a night in a military camp

In Zangilan, in the south, near the border with Iran, we get a feel for Azerbaijani military life. We practice at a shooting range and test drive a tank. It’s certainly unlike any other press trip I have experienced.

In the evening, we share a meal with Azerbaijani soldiers. Stars burn bright out here, unfiltered by city lights.

Our accommodations for the night is in the camp. It feels both safe and surreal. I sleep well.

The next morning, we will get a lesson in landmine clearing. But first…

Aghali: the smart village

Across a small stretch of land, hundreds of families are finally making their way home after decades of forced displacement. The village of Aghali, home to ca. 500, emerges like a model for the future, with solar-panelled homes, fresh sidewalks, and modern schools. Here, amidst the controlled reconstruction, civilians have returned. Commonspace.eu, an independent info and analysis website, sums it up in this article

The village of Aghali is in many ways a pilot project, meant to be one of many. That will continue to be a difficult and costly process. But for the moment Azerbaijan needs to be praised for its achievement.

The right of people displaced by conflict to return to their homes in safe and dignified conditions as soon as is possible is enshrined in international humanitarian law. What is happening in Aghali is a visual example of that right being exercised.

The South Caucasus has hundreds of thousands of people displaced by the conflicts that ravaged the region in the last three and half decades. The latest are the hundred thousand Armenians displaced after the fighting in September. Aghali should be a beacon and a symbol for all of them – a hope for a return home. Whenever a displaced person or refugee returns home – be she or he an Armenian or an Azerbaijani, a Georgian or an Ossetian, every person with a humanitarian conscious should rejoice. This work needs to continue until this problem is relegated to history.

Khudafarin Bridge & Jabrayil: touching the edge of history

We continue to the point where the Republic of Azerbaijan meets the Azerbaijan province of Iran. The Araz River forms the border, marking both a frontier, and a quiet conclusion of sorts.

From the other side of the border, Iranians are looking at us looking at them

The two countries are connected by two ancient stone bridges known as the Khudafarin Bridges. Only one is in working order.

Now, this is not just any bridge. It wasn’t built, you see. It just appeared one day, so the legend goes. In the 13th century. Or the 6th, or the 11th. No one remembers. Not for nothing is it called Khudafarin. ‘God created’.

Spot the gate?

Turns out, the gate to Iran is locked with a simple, corroded padlock.

Climbing over wouldn’t be particularly challenging, except…

Best not try

The Araz River winds its way through arid plains and patches of green…

… forming a mesmerising, intriguing landscape any which way you look.

Landmines

Karabakh is one of the world’s most mined areas, in particular Fuzuli, Aghdam and Jabrayil. More than a million landmines are still active: anti-personnel mines, anti-tank mines –

– and even mines specifically aimed at killing those who locate and disarm mines. Human cruelty knows no bounds.

Since the end of the most recent fighting over Nagorno-Karabakh, clearing landmines and unexploded ordnance has been a major, ongoing effort involving national authorities and international partners. Azerbaijan’s National Agency for Mine Action (ANAMA) leads systematic survey and clearance operations across contaminated areas. International partners work alongside, including the HALO Trust and Mines Advisory Group (both British), as well as the Belgian non-profit, APOPO.

But even though tens of thousands of devices have been destroyed and tens of thousands of hectares have been made safer, there is still much work to do, and it is expected to take years.

TWO JOURNEYS, ONE LAND

Travelling in Karabakh in 2017 and 2024 felt a bit like reading two different chapters written on the same pages. In 2017, the land whispered its history. It was intimate, fragile, human-scaled: a land held together by memory and identity. In 2024, the land announced its future. It was expansive, forward-facing: a land shaped by construction and state-led vision.

One was a world that felt lived-in. The other felt newly reopened. Both are real. Both exist in the history of the same mountains.

Disclosure: In 2017, I was in Nagorno-Karabakh on my own accord. In 2024, it was not possible to visit this territory as a tourist, so I was in Karabakh at the invitation of Azerbaijani extreme traveller Mehraj Mahmudov, with official authorisation from Azerbaijan’s government.

As always, I have complete editorial control of content here on Sophie’s World. Otherwise, this would be meaningless.

THEN & NOW: Nagorno-Karabakh is Artsakh is Karabakh is a post from Sophie’s World