By only removing selected small-diameter trees and leaving some larger trees with diverse spacing, foresters are reducing the density of the trees and returning the forest to a more natural state. © Hannah Letinich

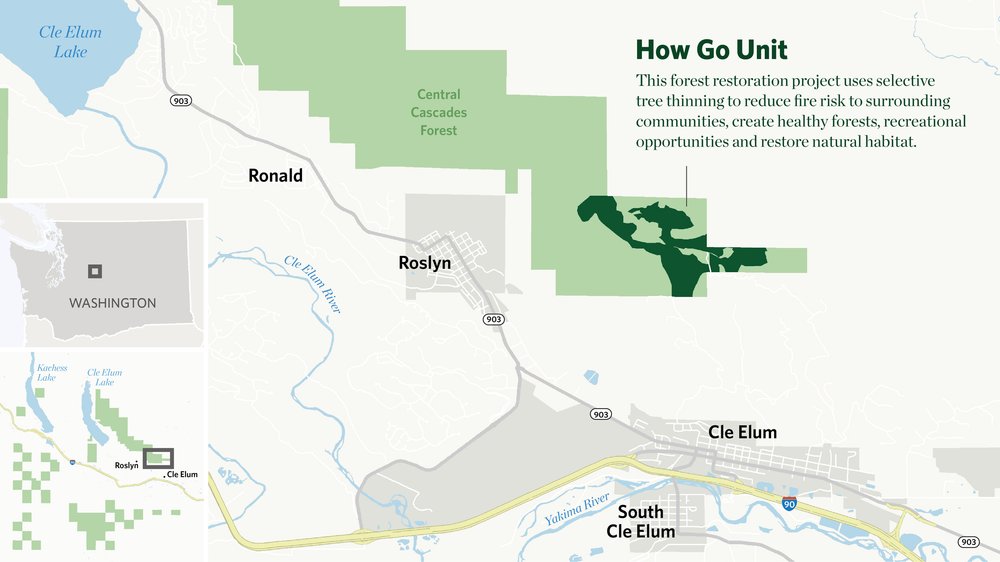

The Nature Conservancy is working on a new and creative forest restoration project on Cle Elum Ridge, called the “How Go Unit,” within the Central Cascades Forest. This “selective thinning” project will reduce fire risk, create healthy forests and support recreational access and natural habitat.

The How Go Unit is a 340-acre experimental site near the towns of Roslyn, Cle Elum and Ronald and is part of the nearly 38,000 acres of Central Cascades Forest land managed by The Nature Conservancy. TNC is ensuring that its forestry practices conserve wildlife habitat, restore watersheds and increase community resilience—the Forest Stewardship Council has certified TNC’s forestry work at the How Go Unit (FSC certification is the highest industry standard for sustainable timber harvest).

“This is really cutting-edge forestry work,” Darcy Batura, forest partnerships manager of The Nature Conservancy, said. “We’re ensuring that we’re meeting the highest standards for sustainability and we believe this project is a model for forest management that can be applied to small-scale forests in Washington and throughout the Western United States.”

Batura is a resident of Roslyn, and she said that these small mountain communities have suffered recently as a result of wildfire. TNC is working to avoid future wildfire disasters by helping to build community capacity to restore the forest and build resilience to climate change impacts like wildfire.

Fire is a natural ecological process. However, fire suppression and exclusion over the last century have made forests dense and susceptible to wildfire. Pests, disease, drought and climate change are exacerbating the problems. Prescribed burning helps to clean up forest floors and nourish the soil. With more open space, trees gain more access to sunlight, nutrients and can grow larger and more resilient to fire.

In a dense forest, fire is fueled by packed trees and vegetation. The plants and small-diameter trees act as “ladders” for fire to climb up to the crown and potentially turn it into a severe wildfire. In 2017, the Jolly Mountain Fire near Roslyn burned more than 37,000 acres of forest land and put thousands of residents in the region on urgent evacuation notice.

“We have not had natural, low-intensity fire on this landscape for over a hundred years,” Kyle Smith, forest manager of The Nature Conservancy of Washington, said. “The thinning and prescribed fire helps to mimic the natural processes…so when we have a fire, it doesn’t kill all the trees due to the lower severity. They are smaller ground fires and more natural.”

A prescribed fire practitioner during a burn on Cle Elum Ridge. Low-intensity prescribed fire removes brush and small diameter trees that could fuel a future wildfire. © Nikolaj Lasbo / TNC

Selective tree thinning is a start for restoring forests to historical conditions. By only removing selected small-diameter trees and leaving some larger trees with diverse spacing (clumps, openings and individual large trees) foresters are reducing the density of the trees and returning the forest to a more natural state. A “masticator” machine is also used to “chew up” small brush and further reduce the fuels that could possibly stoke a large wildfire.

In the coming years, TNC and partners will use prescribed fire to make the forest healthier while reducing the fuels that would cause a large wildfire and improve the safety of the nearby communities.

At the “How Go Unit,” foresters create an inventory about the forest, including acres, species, tree height, etc. Based on the information, a prescription is made and sent to contractors for selective cutting.

Herman Flamenco, conservation forester for The Nature Conservancy, spends days on site to observe and evaluate conditions of the forest for making prescriptions. While reducing forest density, the prescription ensures to maintain special features on the land. For example, a snag, which is a large dead tree, will be left uncut and serve as a potential shelter for animals.

When making these decisions, foresters and managers put both forestry knowledge and creativity into consideration. Flamenco believes there is much to learn from these innovative practices.

“It is a lot like art and science combined,” Smith said.

With the ongoing project, TNC prioritizes hiring local loggers, contractors and workers. The goal is to support the local natural resource economy. As the land is restored to its natural state, communities and smaller businesses can benefit from an increase in tourism and recreational use. However, in the short term, this work relies on patience and collaboration from the snowmobilers, skiers, hikers and mountain bikers who enjoy this land. Residents have been supportive and have followed signs to avoid the treatment site. TNC works to balance active forest restoration with recreational opportunities for residents and visitors.

A local contract forester on-site at the How Go Unit.

“We’re committed to keeping this private land open to recreational use,” Katie Pofahl, community relations manager for The Nature Conservancy said. “And it’s really important that these users pay attention to the occasional closures caused by logging and prescribed burns for their safety and the success of this critical forest restoration work.”

For example, this winter, the How Go thinning work will close Alliance Road, a seasonal snowmobile and hiking trail. Logging trucks on snow and ice make this an unsafe area for winter recreation.

“By protecting and restoring our forest, ” Batura said, “We are maintaining the region’s natural heritage and bringing value to the nearby communities through access to recreation, clean water, safety from wildfire and jobs.”